Air, Climate, and Our Health

By Manushi Sharma, January 28, 2026

The air is changing, and our lungs are paying the price. Even non-smokers are developing lung cancer! As heat, wildfire smoke, and longer allergy seasons worsen pollution, clean air policy becomes a matter of survival, especially for the communities hit first and worst.

According to a December 2020 study in the journal JAMA Oncology, approximately 16% of women in the U.S. newly diagnosed with lung cancer had never smoked. As per the study “the proportion of never-smoking patients with lung cancer was higher in women than in men overall (15.7% vs 9.6%; prevalence ratio, 1.63; 95% CI, 1.58-1.68) and across all age, race/ethnicity, and histology categories”. This number made me uncomfortable. Because if 16% of lung cancer cases aren't linked to smoking, then none of us can opt out of this risk. There's no lifestyle change that guarantees protection when the problem is ambient, caused by pollutants in the air around us.

For this episode of Let’s Talk About Climate focused on #OurClimateOurHealth, I spoke with Dr. David Hill, Chair of the Board of Directors at the American Lung Association. A pulmonary and critical care physician who has practiced in Waterbury, Connecticut, for 28 years, he brings a unique perspective as both a clinician and public health leader on how a changing climate is reshaping respiratory health.

The Air We Breathe

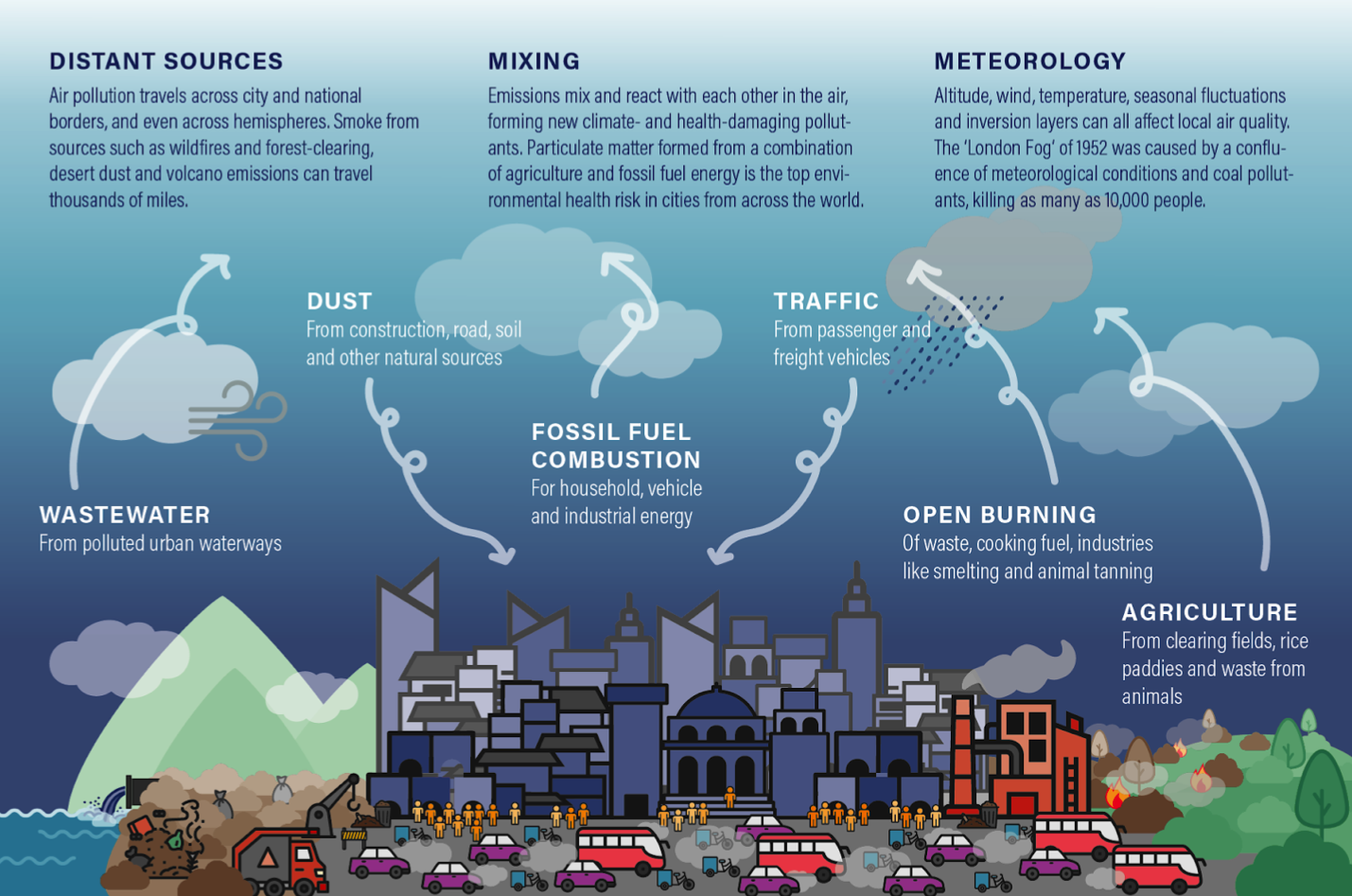

Air is a mix of gases, mostly nitrogen and oxygen, along with water vapor, dust, pollen, and tiny particles from things that burn. These microscopic bits, called particulate matter (PM), come from vehicle exhaust, wildfires, power plants, and even cooking or heating. The smallest of them, PM₂.₅–particulate matter 2.5 micrometers or less in diameter– are so fine they slip deep into the lungs and even enter the bloodstream.

Source: Clean Air Catalyst

As the climate warms, it’s also changing the contents of our air. The heat alters how particles form and move, making pollution more harmful to our lungs. For people with asthma, COPD or Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disorder, or severe allergies, these shifts can turn an ordinary summer day into a health hazard. That’s why doctors increasingly talk to patients about checking air quality and pollen forecasts, adjusting outdoor activity, and managing medications when air quality worsens.

“Each summer brings more patients gasping through the humidity,” Dr. Hill told me. “Allergy season is about a hundred days longer now in some parts of the country: the trees bloom earlier, the pollen stays in the air longer, and we feel it.”

Rising temperatures also trap pollutants closer to the ground, while longer wildfire seasons and shifting weather patterns fill the air with ozone, fine particles, and pollen.

A Problem Without Borders

Our health is defined by the sum of our environmental experiences. Some exposures are within our control, for example, what we eat, how active we are, and whether we smoke. But many are not. The air we breathe, the temperature outside, the pollen swirling in spring, the chemicals that linger in the water – all of it enters us, shaping how our bodies function over time. A few degrees of extra heat can change how plants bloom, how mold grows, and how pollutants linger near the ground. These subtle shifts cascade through ecosystems, altering what we’re exposed to every day. Epidemiologists call this the exposome–the total sum of everything non-genetic that touches us and affects our health. Climate change is adding new stressors and amplifying old ones. Dr. Hill described this exposome that he observed impacting his patients.

“A few years ago, the wildfires on the West Coast were so severe that the smoke traveled across the entire country,” he said. “I was driving in Connecticut and told my wife, ‘You smell that? I think it’s wood smoke.’ You could smell smoke from California in Connecticut that year. Two or three weeks later, we saw a big spike in viral infections. The inflammation makes people more susceptible.”

Air pollution doesn’t stop at state borders or coastlines and has no boundaries. It moves freely, carrying fine particles thousands of miles. Those particles can irritate the lungs, worsen asthma, and even enter the bloodstream. The most visible impacts show up as worsening asthma, COPD (or Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disorder) flare-ups, sinus and airway inflammation, and more respiratory infections. This also makes people with pre-existing heart, kidney, or metabolic conditions especially vulnerable.

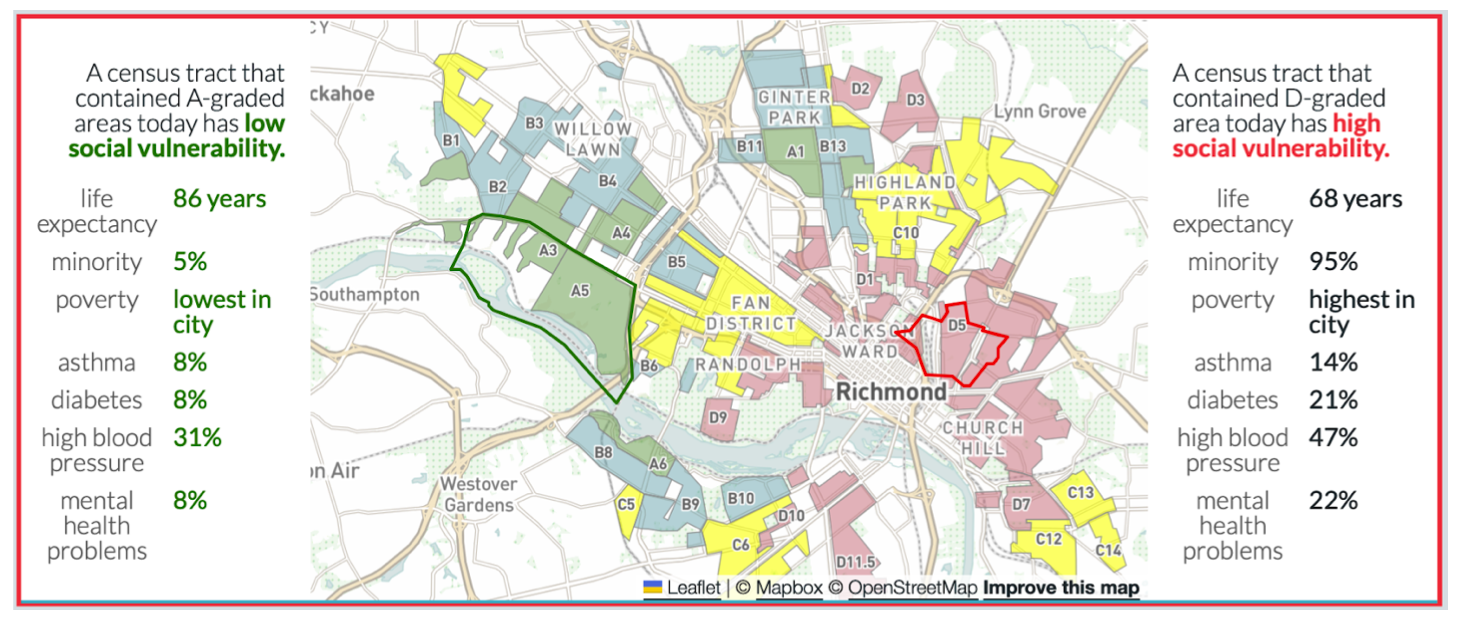

However, not all exposures are equal. “Wealthy people don’t live next to highways,” Dr. Hill told me. “The east sides of cities, where the wind carries pollution, have always been poorer neighborhoods. That goes back to redlining and zoning, and it still shapes who breathes the worst air today.” These neighborhoods have fewer resources, less immediate intervention from governments, and limited access to healthcare.

The Mapping Inequality project, which digitized federal “redlining” maps from the 1930s, shows how government-sanctioned housing policies cemented racial and economic segregation across U.S. cities. Those same neighborhoods, once outlined in red as “hazardous” for investment, are today more likely to have higher poverty rates, less tree cover, and worse air quality.

A 2022 review in the Journal of Urban Health found that formerly redlined areas now experience higher rates of asthma, diabetes, high blood pressure, and poor mental health.

In Detroit, for instance, residents of historically redlined neighborhoods have a life expectancy nearly 18 years shorter than those living in nearby “A-graded” districts.

Source: Mapping Inequality

The State of the Air 2025 report breaks down the major sources of air pollution across the United States. The biggest share comes from

Transportation, including cars, trucks, and diesel engines that emit nitrogen oxides and fine particles.

Electricity generation from fossil fuels follows, releasing sulfur dioxide, mercury, and other toxins from burning coal, oil, and natural gas.

Increasingly, wildfires have become a major contributor, driving sharp spikes in particle pollution and ozone across regions far from the flames.

Together, these sources account for most of the country’s unhealthy air, with climate change adding to the spice mix and amplifying each factor in a vicious cycle.

Fundamental Right to Clean Air

In the 1940s and ’50s, thick industrial smog routinely blanketed American cities. A single week of smog in Donora, Pennsylvania, in 1948 killed 20 people and sickened thousands. Similar events in Los Angeles and New York forced the country to confront what unregulated industry was doing to public health. It pushed Congress to enact the Clean Air Act of 1970, which became the country’s first comprehensive environmental health law. It established the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and, for the first time, required the federal government to set and enforce limits on pollutants known to harm human health. Lead, carbon monoxide, sulfur dioxide, nitrogen oxides, ozone, and particulate matter were formally recognized as threats to life.

The Clean Air Act drove progress in environmental health. New vehicles today emit 98–99% less pollution than their 1960s counterparts. Lead has been effectively eliminated from gasoline, sulfur levels have plunged by more than 90%, and major air pollutants have dropped more than 70%, all while population, economic activity, and vehicle miles traveled have increased.

But in 2025, those gains are under threat. The EPA has proposed repealing greenhouse gas emission standards for the power sector under Section 111 of the Clean Air Act. Under new executive directives, 68 coal-fired plants have been exempted from stricter pollution limits for mercury and toxic metals. The administration has launched what it calls the “biggest deregulation day in U.S. history,” rolling back 31 environmental rules in a single move.

Unfortunately, we rarely treat pollution as the systemic issue it is. It’s easier to frame it as an individual problem, for instance, “make healthy choices,” “drive less,” “recycle more”, or dismiss it as the price of industry or city living. Worse still, while air pollution is indiscriminate, the issue has been politicized. Scientific consensus has become a partisan debate, delaying the policies that could save lives. “The problem isn’t science,” Dr. Hill said. “It’s that too many people profit from ignoring it.” He added, “I’m not anti-capitalist, but a lot of what’s broken in health and public health stems from the same problem - profit before people.”

Policies influence the conditions that determine our health. So if the industrialists lobby for their interests that weaken environmental protections, the consequences impact us in tangible and intangible ways–the air we breathe, the temperatures we endure, the quality of food, and the exposure. As Dr. Hill explained, climate change is even altering the rhythm of common illnesses. “Normally, our viral season follows the school season,” he said. “But now, with longer stretches of extreme heat keeping people indoors, we’re seeing respiratory infections last longer and peak later in the year.” He also added, “We’re seeing malaria again in this country, not because people are bringing it back from travel, but because the environment’s becoming more hospitable for mosquitoes.” We also have enough evidence that while “climate change didn’t cause COVID, but it doesn’t make pandemics less likely… Overpopulation, habitat loss, and heat push people and animals into closer contact.”

Hope and Agency

Despite the policy setbacks and political noise, Dr. Hill doesn’t believe the situation is hopeless. “We still have a democracy,” he told me. “The best way to achieve change is to put pressure on the people in charge, and if they won’t act, replace them.” For him, agency begins at the local level: in towns that pass heat safety laws, in states that enforce air quality standards, and in communities that organize for cleaner transit or greener energy. Progress doesn’t always require sweeping reform; it often starts with the persistence of citizens, clinicians, and local leaders refusing to look away. “People still trust their doctors,” he said. “When we talk about climate and health, it helps patients connect the dots.” Dr. Hill often tells his patients that checking the air quality should be as routine as checking the weather or applying sunscreen.

The science is clear, the solutions exist. At the smallest level, change starts with individual choices. Dr. Hill calls himself “the poster kid for an electric car.” He bought his first one back in 2013, long before it was common, and several friends followed. “You model behavior, and people learn from it,” he said. Small actions don’t solve the crisis, but they can shift the culture. Momentum builds when people see what’s possible.

At the community level, cities are already proving what works. Los Angeles and New York have invested in electric bus fleets and low-emission zones that have cut urban smog. Chicago’s community-led air monitoring projects have pushed for new zoning laws to move industrial polluters away from homes and schools. From Houston to Detroit, tree-planting and green infrastructure programs are cooling neighborhoods, filtering particulates, and reducing asthma attacks.

At the systems level, the Clean Air Act, accelerating the clean-energy transition, and enforcing stronger pollution limits on power plants and vehicles could prevent tens of thousands of deaths each year.

Clean Air = Healthy Population = Thriving Economies

Clean air is a public right, not a billionaire privilege. Protecting our air quality is less about ideology than about collective responsibility.

If you’d like to learn more or get involved, here are some trusted sources and organizations connecting air quality, climate, and health:

American Lung Association: Tips to Become an Advocate

Moms Clean Air Force: a community of more than 1.6 million moms, dads, and caregivers united against air pollution – including the urgent crisis of our changing climate – to protect our children’s health.

Take Action

Take action today by telling Congress to address climate change now!

CLIMATE AND HEALTH SERIES

This piece is part of our ongoing #OurClimateOurHealth Series, which explores how the climate and environment shape our health outcomes. We highlight both the risks and the solutions, showing that climate action is also a public health imperative. Our goal is to inform, inspire, and equip readers, practitioners, and policymakers to safeguard health in the face of environmental change. Explore other stories from the series HERE.

Change The Chamber is a nonpartisan coalition of young adults, 100+ student groups across the country, environmental justice and frontline community groups, and other allied organizations. To support our work, donate or join our efforts!