Womb with a View (of 1.5°C)

By Lydia Samuels & Manushi Sharma, October 2, 2025

Extreme heat is putting pregnancies at risk, increasing the chances of stillbirth, preterm birth, and lasting health complications. At the same time, rising temperatures are making decisions about whether and when to have children even more uncertain.

Source: The Health Policy Partnership

I (Lydia Samuels) grew up in Jamaica, where heat is an old companion. We know its moods—how it clings in the mid-afternoon, how it softens in the evenings when the sea breeze drifts inland. But in recent years, that familiar warmth has sharpened into something else. The air feels heavier, the shade less forgiving. Even for those accustomed to tropical sun, there’s a difference between heat you can live with and heat that makes living harder. With summers now marked by intensifying heatwaves and record-breaking temperatures, extreme heat is a growing public health challenge. Extreme heat is a problem without borders. While the geography of risk might look obvious—places like Jamaica, Nigeria, or Bangladesh facing higher baseline temperatures—the truth is that climate change doesn’t respect borders. The summer of 2023 saw Phoenix, Arizona, endure 31 consecutive days above 110°F. In France, a heatwave in 2019 claimed over 1,500 lives.

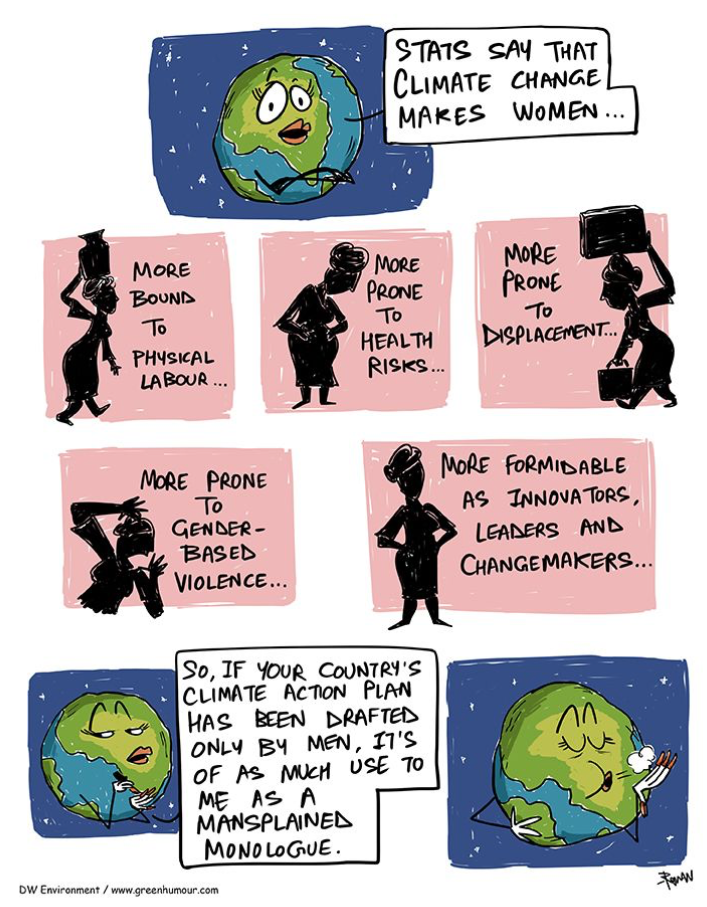

Source: Rohan Chakravarty

In recent decades, another shift has unfolded quietly in the background; the world is simply having fewer babies. Fertility has fallen from an average of nearly five children per woman in 1950 to around 2.3 today—close to the level needed just to maintain population numbers—yet declining steadily in nearly every region worldwide. Across Europe and North America, that average dips even lower to about 1.4 and 1.6, respectively. And while some of this reflects longer lifespans and greater reproductive agency, it’s also shaped by growing anxiety about bringing children into a world where climate hazards such as sweltering heatwaves are becoming more frequent. These challenges of potential pregnancy in a warming world become more immediate when I hear my own mother’s memories of her pregnancy with me in the dead of the Caribbean summer. She never dwells on morning sickness or cravings, “It was just hot—all the time.”

Pregnant bodies, it turns out, have their own climates and are particularly sensitive to heat. Prolonged exposure to high temperatures doesn't just make life uncomfortable; it can increase the odds of stillbirth, preterm birth, and low birth weight. These aren't distant warnings—they're already showing up in data pools from Brazil to the United States. Common heat symptoms– dizziness, fatigue, dehydration–are unpleasant enough. But for a body already running its own internal summer, as even a single day of extreme heat (above the 95th percentile of mean temperature) can increase the risk of preterm birth, stillbirth, or low birthweight. A 2025 meta-analysis covering nearly 200 studies across 66 countries found that each 1°C rise in heat exposure increased the odds of preterm birth by about four percent, while exposure to a full-blown heatwave raised it by 26 percent. Heat also increases the risk of congenital anomalies and gestational diabetes. Another study pegged a 10 percent higher risk of preterm birth when temperatures exceeded the 99th percentile. And just as climate disasters disproportionately affect marginalized communities, so too does heat threaten maternal health more severely where social and environmental inequalities exist.

Presently, Jamaica has one of the lowest fertility rates globally, with women having an average of just 1.36 children in their lifetime, well below the replacement rate of 2.1. This decline is shaped by economic pressures, limited access to affordable housing, and growing uncertainty about starting families amid rising costs and unstable livelihoods. In 2024, Health Minister Dr. Christopher Tufton urged Jamaicans to consider having more children “if they can afford to,” reflecting government concerns over the nation’s aging population and shrinking workforce.

Yet these fertility decisions do not occur in a vacuum—they intersect with a climate that's becoming increasingly hostile. Jamaica, like other Caribbean nations, is experiencing rising temperatures and more frequent extreme heat events. In 2023, the region recorded its highest mean temperature in over a century, with prolonged heatwaves straining public health systems and amplifying vulnerabilities, particularly among pregnant individuals. Heat-related illnesses surged, increasing the prevalence of diseases such as dengue fever, highlighting the direct threat of extreme heat to health and healthcare capacity.

The complications do not stop there. Extreme heat during pregnancy has been linked to serious neonatal outcomes, including fetal distress, neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) admissions, fetal growth restriction or low birthweight, congenital birth defects, and sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS). Conditions such as congenital anomalies, low birth weight, and fetal growth restriction can shape a child’s health trajectory for life, affecting development, learning, and overall well-being. These risks collide with social realities. The Jamaica Gleaner has called heat stress an “invisible killer,” especially for working women in sectors like agriculture, teaching, and informal urban labour.

When extreme heat threatens both maternal health and a child’s future well-being, decisions about family planning become even more fraught. The same rising temperatures that endanger pregnancies also compound the economic and social pressures that already shape fertility choices. The uncertainty of raising children in a warming world discourages couples from expanding families, as the immediate concerns of survival and stability often outweigh long-term aspirations. In this context, government calls to increase fertility collide with the physical realities of a climate in crisis. Without measures to address heat exposure, strengthen public health systems, and provide climate resilience, the challenges of conception and safe pregnancy may continue to outweigh the desire—or the feasibility—of having more children. With disproportionate impacts on single mothers and low income households.

Solutions exist. Even though our broader response to maternal health in the face of climate change has been uneven, there are powerful examples of innovation and care leading the way. Short-term measures—like community cooling centers, public hydration stations, and modified work hours—can make immediate and necessary differences. For instance, in Ghana, mobile antenatal outreach reduces pregnant women’s exposure to the sun and makes essential care more accessible. Long-term strategies, such as heat-resilient healthcare infrastructure, climate-informed maternal health guidelines, and gender-responsive adaptation policies, are essential. At a systems level, legislation like the Protecting Moms and Babies Against Climate Change Act (introduced in the U.S. Congress in 2021) shows how governments can act: funding county-level partnerships to reduce risks, integrating climate-health training into medical education, supporting research through a dedicated Birth and Climate Change consortium, and mapping high-risk areas to protect mothers and infants.

When I think about maternal health and climate change, I return to a truth I’ve carried since leaving Jamaica for the U.S.: vulnerability isn’t only about place. It’s about the systems that determine who can adapt, who gets left behind, and whose well-being is treated as expendable. Heat may be universal, but the safety nets are not.

Importantly, these aren’t just for the Global South. If we want expectant mothers—whether in Kingston or Kansas—to handle the rising heat, our efforts must be as global as the crisis itself. Because in the end, climate change may not discriminate, but our preparedness certainly does.

If you or someone you know is pregnant and concerned about heat, air quality, or other climate-related health risks, the American Public Health Association’s Factsheet is a helpful resource.

CLIMATE AND HEALTH SERIES

This piece is part of our ongoing #OurClimateOurHealth Series, which explores how the climate and environment shape our health outcomes. We highlight both the risks and the solutions, showing that climate action is also a public health imperative. Our goal is to inform, inspire, and equip readers, practitioners, and policymakers to safeguard health in the face of environmental change. Explore other stories from the series HERE.

Change The Chamber is a nonpartisan coalition of young adults, 100+ student groups across the country, environmental justice and frontline community groups, and other allied organizations. To support our work, donate or join our efforts!