The Gambia: A Small Nation with a Big Fish Problem

By Erika Pietrzak, November 21, 2025

Foreign overfishing and fishmeal factories are stripping The Gambia’s waters, driving up food prices, and polluting coastal communities. Weak regulation and corruption have turned a basic food source into a tool of exploitation.

Fishing in West African countries is one of the largest portions of most nation’s economies. The continent's food security struggles with its booming population endangers the over 1.5 billion people in Africa. Fish is an essential resource for meeting the population’s needs and keeping west Africa’s population alive. Not only does the fishing industry provide this crucial sustenance, but brings in tourism and other economic activities that help uplift west Africa’s economy further. However, overfishing and illegal fishing is disrupting this crucial economy. According to Amnesty International, about forty percent of caught fish on the West Coast of Africa is caught illegally. One of the nation’s experiencing the most turmoil and degradation is the small, skinny strip of over two million people surrounded by Senegal known as The Gambia.

The Gambia’s eighty kilometers of coastal towns rely heavily on fishing for their protein intake as well as their economic activity. There are five hundred different species living off the coast of The Gambia and the fishing sector regularly makes up more than ten percent of the country’s GDP since 2019. In 2022, more than three hundred thousand people were employed in The Gambia by the fishing industry. The industry has grown rapidly due to foreign investment, tax exemptions, and lax regulation of illegal fishing.

One coastal town is Sanyang, located in the northwest corner of the country and home to seven thousand people. The town is a hub for tourism in the country, which the fish industry is a large supporter of. However, the town is now majority of foreign fishermen, the bulk of whom are from Senegal (whose population has soared since 2018), who exploit the country’s finite resources and export them for larger profits. Trawlers are overwhelmingly foreign fishers “only seven Gambian-owned vessels equipped for industrial fishing, with only four operational, although there are Gambians working on foreign-owned ships” in 2019. Today, 90 percent of all legally operating fishing boats in The Gambia are foreign owned. Because of how much fishing is done, fish end up discarded and thrown away, meaning some of the environmental degradation is quite literally for nothing. This has lead to a potent smell that has decreased ecotourism in the area.

Today, foreign industrial trawlers, fishmeal, illegal fishing, and fish oil factories all place significant pressures on The Gambia and Sanyang as multiple industries fight over limited resources. This exploitation “is done with absolute impunity, opaquely, and with the approval of the Gambian Ministry of Fisheries.” Inaction has now led to food insecurity, malnutrition, and an increase in diseases like malaria, pneumonia, and diarrhea.

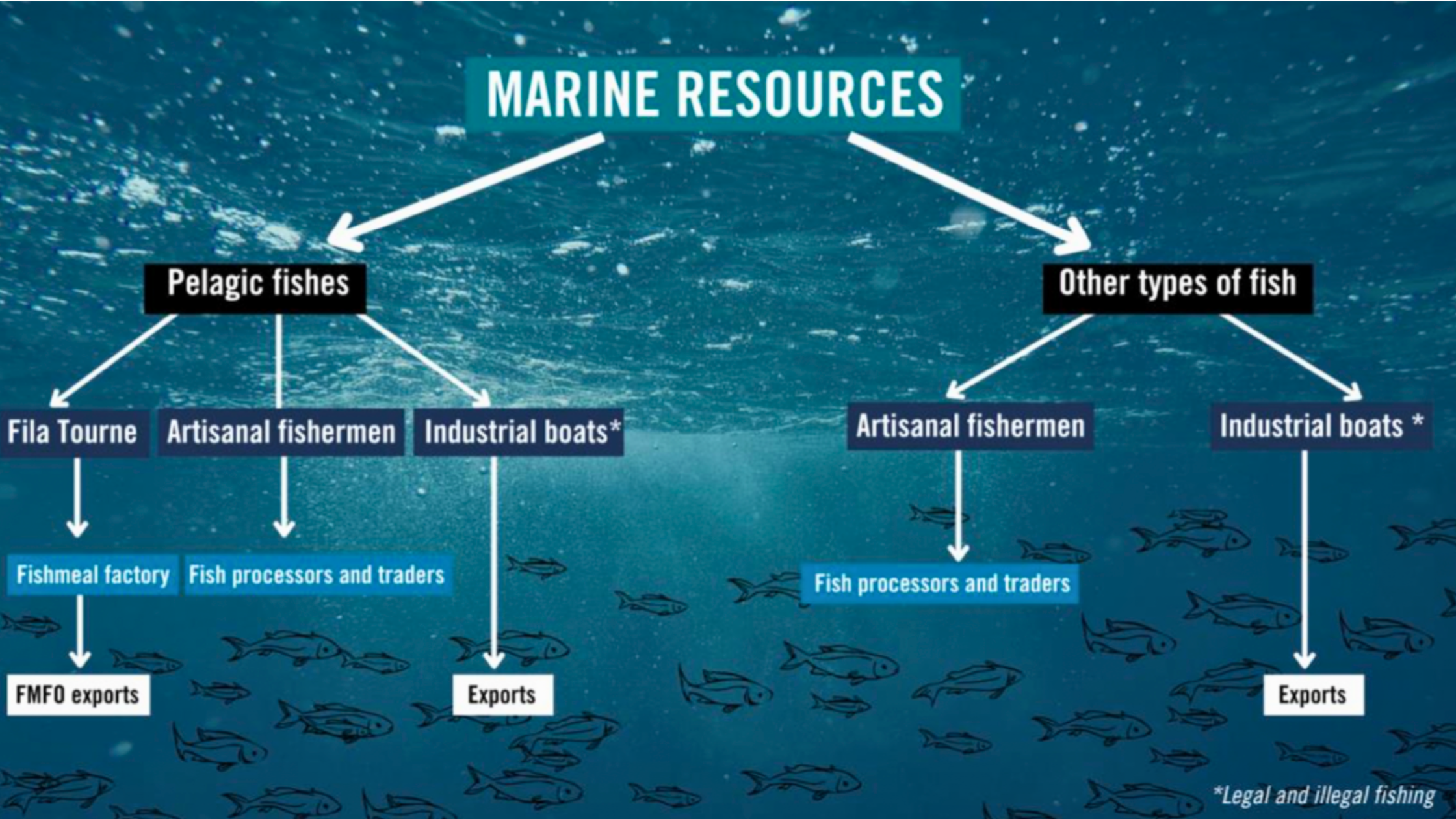

Source: Amnesty International

Illegal fishing causes “Gambia, Mauritania, Senegal, Guinea Bissau, Guinea, and Sierra Leone [to] lose USD 2.3 billion annually.” These boats not only limit the fish stocks available for legal fishermen, but artisanal fishermen have documented instances of foreign boats coming closer to shore than legally allowed to capture more fish and cut the local’s fishing nets. They also fish without regard for replenishment of the ecosystem to reach the most economic gain and prevent others from doing so, a concept known as the tragedy of the commons, by using small-meshed fishnets that capture juvenile and adult fish alike. This tragedy empties waters “irrespective of regulations forbidding them to fish in a zone reserved for artisanal fishermen, thereby forcing them to go fish further and longer into the sea.”

Due to exportation, in-country prices of fishes are rising, making most locals unable to afford the food in their backyards. Restaurants are struggling to stay in business and provide for their customers as the popular fish become harder to find. One restaurant owner told Amnesty International “If the coronavirus has bankrupted businesses, the fishmeal factory is doing worse than that […] We know corona would last a particular moment in time but the fishmeal factory we do not know when we are going to be out of the situation.”

Between 2016 and 2018, three fishmeal and fish oil factories were built in The Gambia, requiring more fish to produce the same amount of product. This happened after the country freed itself from a dictator and opened itself to foreign investment. All of the factories were opened by China and the foreign country has caused significant corruption in The Gambia’s coastal cities.The transparency of these industries in the country is lacking significantly with much of the products being shipped away from the country. Fishmeal is of particular issue as it takes 4.5 kilograms of fish to produce one kilogram of fishmeal. This fishmeal is used for building aquaculture, destroying fish in one area to feed fish in another. The Bolong Fenyo Wildlife Reserve lagoon was found completely pink one day in 2017 because of all the dead animals. Arsenic, phosphates, and nitrates caused a massive die off that showed visual impacts that many environmental issues cannot show. Protests and revolts broke out, including damaging the factories. However, protesters were swiftly arrested, factories repaired, and the Chinese flag soon flew outside.

Another major factory is that of Nessim Fishing And Fish Processing Co., who began operating in the country in 2018. Their first year of operation saw them suspended for six months due to improper discharge of wastewater as they dumped waste 35 meters into the sea rather than the required 350 meters. The company was also dumping their waste into roads and vegetable gardens, which led to many female agricultural workers on the coast complaining to Amnesty International. Not only was this an environmental hazard, but the Nessim company significantly endangered public health. Though they have built a proper wastewater treatment plant since, they were fined twice in 2020 for not properly treating their wastewater.

Source: Africa Defense Forum

Nessim was the catalyst for more protests in 2021 that occurred after one factory employee allegedly killed a local fisherman from Sanyang. Substantial fishing equipment and part of the factory building were burned with over fifty people arrested and fourteen charged with “conspiracy to commit misdemeanour, unlawful assembly and riot, and five others were charged with going armed in public, shop breaking, theft, arson, damage to property, conspiracy to commit arson, unlawful assembly and riot.” Several arrestees alleged torture while detained, being forced to sign documents without knowing their contents, and other ill treatment, one of which is still pending in court.

Since the growth of the fishing industry in The Gambia from 2015 to 2019, environmental damage has significantly grown. Factories require 500 tons of fish per day, which requires large trawlers that disrupt the ocean floor. This disruption not only harms the habitat for marine life, but also affects ocean currants. Between 2019 and 2022, Sanyang beach was reportedly crowded by dead fish on three separate occasions with other sources reporting multiple other instances, not just an eyesore but also a public health hazard.

Take Action Now!

Support universal ratification of the High Seas Treaty.

ENVIRONMENTAL JUSTICE

At Change the Chamber, we recognize the disproportionate impacts of pollution, climate change, and other environmental harms rooted in the legacy of systematic oppression and discrimination. We must promptly address these environmental injustices to create a sustainable and equitable future for all. We encourage you to engage with this vital issue. To read our full statement or view more of our environmental justice work, click here.

Change the Chamber is a nonpartisan coalition of young adults, 100+ student groups across the country, environmental justice and frontline community groups, and other allied organizations. To support our work, donate or join our efforts!